....

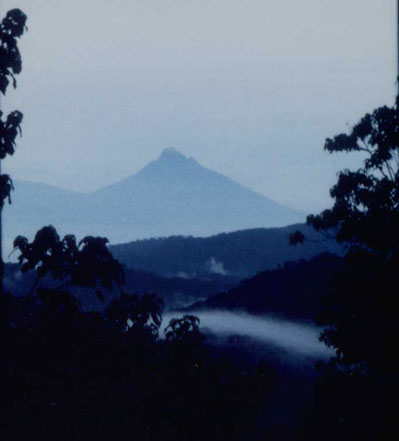

Kisoro is on the junction of the borders of Uganda, Rwanda and Zaire. Geological boundaries meet here, too - manifest in the Virunga Volcanoes, over 4,000 meters in height and renowned for mountain gorillas, spectacular scenery, refugee problems and occasional eruptions. The town has a frontier flavour - two bumpy streets of black tuff and cinders, trading stores and colorful picket fences. Herons’ nests sway in the treetops and urchins kick rag footballs, while cows and goats munch domestic trash.

Our team from the Institute of Tropical Forest Conservation (ITFC) was en route to Mgahinga Gorilla National Park to survey Kabiranyuma Swamp, a bog between two of the volcanoes. Since the 1950s, Kabiranyuma's natural outflow had been channeled down the slopes into a water reticulation system supplying thousands of people. After years of deterioration it was now proposed to upgrade the entire system to improve the yield. Concerns had been raised about the impacts of hydrological changes on the swamp's ecology. ITFC’s job was to assess the conservation importance of Kabiranyuma and propose ways to minimise any ecological damage that might result from the water scheme. In this phase of the investigation we would survey vegetation, describe key habitats and make a provisional list of the large mammals and amphibians in the affected area. Our small team included Stephen, a Ugandan frog expert, Maryke the ITFC ecologist, and Caleb and William, field assistants.

Working in Kabiranyuma would not be straightforward. The swamp lies in a saddle between volcanoes Muhavura and Mgahinga, at around 3,000 meters above sea level, reached by a taxing walk up the steep flanks of the volcanoes. Food and equipment comes up on the heads of

porters. The watershed of the swamp is on the Rwandan border and our survey would need security clearance from the Rwandan army outpost just across the frontier. The weather up there would probably be cold, wet and gloomy.

Arriving in Kisoro late in the afternoon we called at the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park office to meet the park staff and confirm preparations for the survey. The warden said he would dispatch a ranger to the Rwandan side to inform them of our presence. Then we moved a short way up the road to the Traveller's Rest Hotel, a ramshackle place where there was nothing to do but eat dinner and lounge on the prehistoric sofas before turning in for the night.

Before dawn we were awakened by gunfire. The reports sounded like shotgun blasts and seemed to be moving round the town. Perhaps it was the police chasing some thieves, I thought. But shooting was still going on later when, unsure of what else to do, I obeyed the herd instinct and went for breakfast. The others were already in the dingy dining room at a table near the window. Hovering morosely, the hotel manager could not tell us what was happening. Without conviction he suggested it might be a training exercise at the army barracks over the road; but he looked as though he feared worse. The gunfire came closer and we awaited our tea and toast in subdued and pensive mood.

At about 0830 I decided to go to the park office to find out what was going on. Outside it was clear and sunny with just a few clouds visible up on the volcanoes. The crack of the loudest gunshots made me wince and start but in such bizarre circumstances I was unsure whether I should be frightened. The police station was on the way to the park office and I took the chance to move away from the noise to ask them what was happening. They didn't know. Was it a training exercise? They didn't think so; in fact they suspected there might be some sort of problem.

I walked on to the park office. All doors to the street were padlocked shut and no-one was around. Maybe I was too early. I sat on a bench outside to wait. After a while two men came up the street, heading for the police station. One advised me, “Probably the office will not be opening soon because the army barracks is under attack by rebels”.

Returning to the hotel, I found the ITFC crew still around the breakfast table. Through the window we looked in the direction of the barracks. Since I had been away a few armed men had emerged on the road outside the hotel. Dressed in civilian clothes they seemed at ease, strolling about in plain view and occasionally crouching with their backs to us to direct bursts of fire towards the gaggle of mud and block houses between them and the barracks. Stephen suggested that we should move away from the windows, and moments later the five of us were crouching in a windowless scullery annex next to the kitchen.

We were there for about ten minutes listening to the shooting before a character with a hat materialised in the bright frame of the doorway. Others behind him. Someone pointed at Stephen, shouting, "You - Mtutsi! Come out!". This seemed bad. It would be a summary execution. Time began to run slowly. Stephen didn't move, protesting vehemently that he was not Tutsi. Nobody moved. I listened to my voice telling them that he wasn't a Tutsi.

The intruder turned to me, still speaking in English, "Who are you? Where do you come from?"

"I'm Simon from ITFC. I'm British. These people are researchers"

"Come outside. Whose are these vehicles? We are taking them."

We shuffled nervously into the sunlight, next to the parked cars. The chief bandit was fairly tall, and slim with fine features. He had a moustache like Eddie Murphy and he smelled of Imperial Leather talcum powder. On his head was a hat made from the shiny brown sheath of a banana stem - it was folded to form a sort of Hussar's hat, complete with a chinstrap. He was wearing army boots and camouflage trousers. He had a lunatic charisma.

There were four or five followers with him. They had AKs and RPGs. They were unreadable, inscrutable and probably unpredictable. They looked nastily stoned. One, squat and stocky in a blue football shirt and shorts, a rocket launcher over his shoulder, gestured at Stephen, "Shoot this Mtutsi!". But his companions' attention was on the vehicles now and they paid him no heed.

Banana Hat spoke. "Brother Simon, you are British. You know, there is no need to worry. Of course we don't want to fight and we don't like bloodshed. In fact I remember the British gave Ugandans our independence without bloodshed: it was just a matter of signing some papers. But these politicians in Uganda today are not like that; they are sucking the people dry. They are killing us so we have to destroy them." He indicated his mates. "These friends with me - they are from the Uganda army. We want to remove these killers in Kampala. We will be there in a week's time."

"Who has the keys for this vehicle?," he demanded, looking at a white Land Cruiser pick-up. The owner was still in his room, bathing. This performance required jerrycans of hot water ordered well in advance and it seemed that an outbreak of war would not interrupt this man’s ablutions. But now he appeared, in sandals and a towel, still wet, with the keys to the Cruiser. He was brown, tall, slim and urbane. To the challenge, "You are a Mtutsi!", he retorted, "Yes I am. I am a Mtutsi. Me, I am a Mtutsi!". Nothing happened.

"Give me the keys to this vehicle", said Banana Hat. The Mtutsi claimed that the car didn't work. One of the bandits was the elected driver. He took the keys and tried. The engine turned reluctantly, started but conked out after a few meters. The driver informed Banana Hat that it really wasn't a runner and attention turned to the only other car: ITFC's Land Cruiser station wagon.

"We will take this one - give us this vehicle."

I felt I should put up some token resistance. "Please don't take it. I'll lose my job if this car is destroyed".

"Don't worry. We will bring it back in about four hours. There is no problem. Give me the keys and empty the car."

The vehicle was packed to the roof with camping gear and rations. Fully expecting the car to be blown to smithereens, I was surprised and relieved that we would at least be allowed to retain our field gear. Helped by the others I started unloading the vehicle, using the opportunity to try to think. There seemed to be nothing we could do. I clambered onto the roof rack to remove the last of the gear, handing it over the side to William and Caleb, who were working like automatons, blank-faced and numb. Banana Hat remarked approvingly on our smart new jerrycans and gumboots but noone tried to take them from us.

"You don't need to worry about the car. We will bring it back later."

"Please don't take it. It's going to get damaged. It's not bullet proof you know ".

"None of us is bullet proof, Brother Simon"

I handed the keys over. The Cruiser had an immobiliser, so when their driver turned the ignition key nothing happened. I wondered if I could lie that this car was also broken. The driver turned a baleful eye on me - "You - start it now ". I complied meekly. He reversed out, his mates piled in and off they lurched, gun barrels protruding from the open back doors.

Outrage and impotence mingled with relief that the crazy bastards had gone for the time being. Thinking of insurance claims, I headed back to the police station to report the theft. The gunfire seemed to have subsided. At first I could find noone in the station. I said I wanted to make a report and waited for ten minutes while the officer found his red report-writing pen. He asked what I wanted to report. I said car theft and gave him the details. He objected, "But it is not theft". That was absurd, I protested – surely removal of the car by five armed men qualified as theft, and I insisted he record it. He wrote grudgingly, pausing to repeat, "It is not a theft - your vehicle is there. Look", pointing with his chin across the road. The cruiser was in the compound of the barracks, being loaded up with something.

While this went on, I became aware of a radio operator working behind a wire grille in a kiosk adjoining the office. He was telling someone, "We don't know what is happening. We cannot confirm what has happened but the situation is now safe on the ground." The reaction from the other party must have been sceptical, and the operator reiterated "The situation on the ground is under control, our men are patrolling in the town".

I went back to the hotel. Maryke and I decided to go back to the park office to see if they were open. The others stayed in the hotel. The office was still locked and shuttered. A man was standing by a concrete pillar a little further along the verandah, seemingly calm and observing events with interest. Suddenly the ITFC Land Cruiser appeared at the junction leading from the barracks. It stopped by the police station, the occupants apparently shouting to the police inside, then moved towards us and halted again opposite our position. Now there was a heavy machine gun fitted on a tripod on the roof rack, manned by two men festooned with ammunition. The WWF cuddly panda logo seemed somewhat incongruous. Banana Hat was in the passenger seat, closest to us. He called, "Brother Simon we don't want to frighten people. This is a peaceful takeover. We will assure everyone's safety. But if the Local Defence Unit try to attack us we will have to kill them. We are telling them to remain calm."

The car moved off up the street, pausing occasionally, presumably to broadcast this message. I heard snatches of "...stay in your houses...nothing to fear...LDU...we will give them fire!"

Meanwhile, sustained heavy firing began around the barracks. We could see people dodging about in the bushes and on the hillsides overlooking the barracks, firing at unseen targets. A man in a black greatcoat was moving up and down the hillside confidently, shooting at someone. He looked as if he had done this before. I was instinctively ducking at the noise of gunfire now, especially the "wind in the wire" humming and twanging sounds of shots which I assumed were flying over our heads. I expected chunks to fly out of the plasterwork in the façade of the building behind us. But it seemed there was no way to get out without exposing ourselves even more. I had had enough by now, but Maryke seemed to be taking it phlegmatically.

The ITFC Cruiser came barrelling back down the street and stopped again in a gritty cloud of black Kisoro dust. Banana Hat shouted, "You see, now they are attacking my people. We will just have to kill them all. Brother Simon, do you think we should kill them now?" Lamely I responded that perhaps they should try talking it over peacefully. They roared away, teetering round the corner towards the barracks and disappeared from view. I listened for the sound of their heavy roof-mounted gun but couldn't detect it. It was suicide. In that enfillade the men at the gun on the roof would be sitting ducks.

Rwandan soldiers were now sweeping through the town. Gunfire lessened as the skirmishers moved into the scrub and bushes between the houses near the road to Zaire. The smart red-bereted Rwandans seemed well organised and once they had moved past our position it felt as if things were secure again. A composed and self-assured officer asked us who we were and what we up to.

The townspeople emerged from wherever they had been hiding. Soon most of the population was standing round the ITFC cruiser. It had made it about 100m past the Traveller’s Rest on the road towards Rwanda before it was halted and the occupants killed. The badly-scared Local Defence Unit people immediately went back into character, officiously and pompously insisting that we could not see our vehicle although already there were several hundred onlookers on the scene.

So we were unable to approach the cruiser until the next day. The bodies of eight of the rebels were spreadeagled nearby on the football pitch, a guard posted to keep the dogs off them. The car was riddled with holes and the windows smashed. Three of the tyres were flat but, we discovered later, not shot out. Perhaps they had shot the driver and machine gun crew from a distance and finished the rest at close quarters. There was a glutinous dark pool of blood in the back, and the area was strewed with packets of condoms. Moving around to the passenger side I found the banana hat, crumpled on the grass.

Epilogue

We eventually towed our vehicle back to the police station, where we left it until a mechanic could be sent to get it back on the road again. On arrival he found that the hub and shaft assembly from the front axle had disappeared, but luckily there was a man in town who had for sale just the thing we were looking for.

ITFC went back to Mgahinga in June 1996 and completed the survey without incident apart from hearing one or two shots from Rwanda.

Simon Jennings 22/7/97